Dear Reader

Painter, photographer, sculpturer Michelle Amerie created the Irises that open this issue of the Disability Digest. In her spare time she is a spokesperson for the MS Society which includes rappelling down high rise buildings in her wheelchair. During the pandemic Michelle converted her original art pieces onto face masks. Check out her extensive selection and order details here. Wearing a beautiful piece of art is the perfect antidote to the pandemic doldrums. It’s also an affordable luxury.

Also featured in this issue are Motown legend Stevie Wonder, politician David Smith, autism researcher Michelle Dawson and disability justice pioneer Stacey Milbern.

You can help influence the future by correcting the past. Send your comments and suggestions via this form. And if you like what you’re reading please spread the word.

Enjoy– Al

PS: check out my new podcast series The Power of Disability. This week’s guest is artist Carmen Papalia. His performance art focuses on the nub of democracy, caring trusting relationships. If you want a sense of where the disability movement is heading check out our conversation.

“The heart of Disability Justice,” says Papalia “is mutual aid, which means building a capacity for care that isn’t otherwise available.”

May 13 is the birthday of musical legend and Motown sensation Stevie Wonder (1950). Wonder was just 11 years old when Motown signed him to a contract in 1961. Since then, he has used his voice to earn more GRAMMY awards than any other solo artist. He also won an Academy Award for best song (I Just Called to Say I Love You), the Polar Music Prize, and the Montreal Jazz Festival Spirit Award. Wonder is one of the first artists to secure his artistic freedom by writing, producing, arranging and performing his own songs. Songs in the Key of Life is his best selling and most critically acclaimed album. “Life has meaning only in the struggle. Triumph or defeat is in the hands of the gods. So let’s celebrate the struggle,” he says.

Wonder now uses his voice to make the world more inclusive. He was a strong advocate for ending apartheid in South Africa. He was instrumental in the campaign to make Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a U.S. national holiday. In fact he put his career on hold for three years to lead rallies in support of the proposal. “As an artist, my purpose is to communicate the message that can better improve the lives of all of us,” he told a crowd in Washington DC in 1981. The first official Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, was held on January 20, 1986. It was celebrated with a concert, headlined by Wonder. “If we cannot celebrate a man who died for love, then how can we say we believe in it?” he asked the crowd.

Since 2009, Wonder has been a United Nations Messenger of Peace with a focus on persons with disabilities. “The more people who are doing things that make a difference and are part of this world of inclusion,” he said, “the smaller the world gets of people who are not committed and ultimately we will end up with a world of inclusion.”

Wonder had a kidney transplant in December 2019. “I feel like I’m about 40 right now,” he said. “Now I want the world to get better,” he added. “I want us to get beyond this place. I want us all to go to the funeral of hate. That’s what I want.”

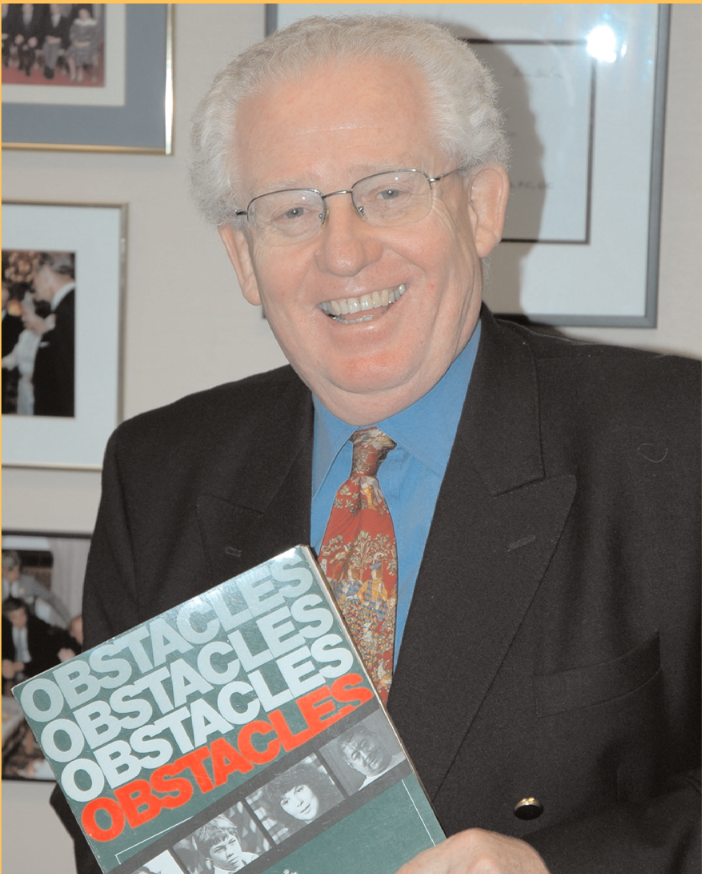

May 16 is the birthday of Canadian politician and Senator, David Smith (1940). In 1981 he chaired Canada’s first parliamentary committee on disability. It produced Obstacles: The Report of the Special Committee on the Disabled and the Handicapped.

Although Smith did not have a disability, he was also instrumental in ensuring disability was added to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom. He actively lobbied behind the scenes. When former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau told him disability would be included, Smith told an interviewer he was, “a bucket of tears.”

Smith died in February 2020, at the age of 78.

On May 17, 2017, self-taught autism researcher Michelle Dawson received the Order of Montréal. Her citation read in part: “She has documented the poverty of scientific and ethical standards in autism intervention research, and the resulting harm to autistic people…she believes that in research, as elsewhere, autistic and non-autistic people should work together as equals.” Dawson describes herself as an “off message autistic researcher” and emphasizes that “Almost everything about me on Wikipedia is wrong.”

She is a member of Montreal psychiatrist Laurent Mottron’s university research team even though er only academic credential is a high school diploma. Now she has an Honorary Doctorate. She and Mottron have co-authored more than a dozen papers and several book chapters. Their approach to research complements each other. She is bottom up, finding ideas from the facts. He is top down, coming up with an idea and then checking to see if the idea fits the facts. People describe them as the odd couple.

“Dawson knows the scientific literature as well as anyone. She is a library in the field of autism and cognitive sciences,” says Mottron. He credits Dawson with challenging his scientific perception of autism. And shifting his view that autism is a disease to be cured rather than a different way of looking at the world that should be honoured.

“Accurate information is always good for autistics,” Dawson wrote on her blog. “Only when people with differences have legal and human rights can they be ethically researched and ethically helped. Otherwise, it is neither ethical or scientific.” She added, “You can say anything is evidence-based if you set the standards of evidence low enough.”

In an article titled The Misbehaviour of Behaviourists she wrote, “We are in a society in which autistics have rights only if and when we resemble non-autistics. This is like being black in a society where blacks have rights so long as they become white.

On May 19 writer, activist and disability justice pioneer Stacey Milbern was born in Seoul, South Korea (1987). Milbern had muscular dystrophy and described herself as “just your everyday queer corean girl living in the south.” She grew up in North Carolina and moved to the San Francisco Bay Area when she was in her twenties. She became the director of programs at the Center for Independent Living, Berkeley and was appointed by President Obama to the President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities. She also became a founding member of the disability justice movement. Disability justice is a practice and a framework in which disability is understood both as an embodied experience and a socially constructed experience.

Milbern believed disabled people are resourceful out of necessity. During the early months of the pandemic she organized the Disability Justice Culture Club to help homeless people protect themselves against Covid. “The world literally isn’t made to house us …” she said. “So we get to be really creative problem solvers and aren’t constrained to boxes.” Disabled people often have solutions that society needs said Milbern. “We call it crip — or crippled — wisdom.”

Milbern died on May 19 due to complications from surgery. It was her 33rd birthday. Her New York Times Obituary reprinted her quote from a previous interview: “I would want people with disabilities 20 years from now to not think that they’re broken,” she said. “You know, not think that there is anything spiritually or physically or emotionally wrong with them.”

Did you know?

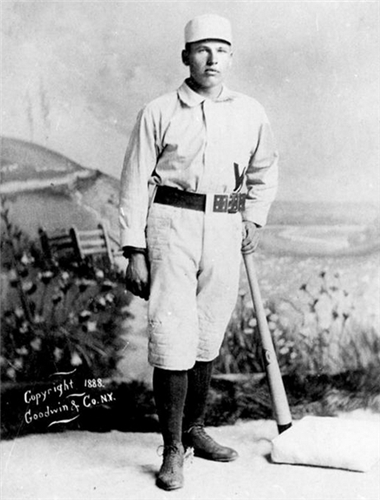

Hand signals in baseball were invented by William Hoy in the late 1800’s. Hoy was a talented centre fielder who holds the record for throwing three runners out at the plate in a single game and hitting the first ever grand slam home run in the American Baseball League. He was also deaf. That meant he couldn’t hear the umpires call and had to pause to ask his coaches. While awaiting their answer the pitcher often sneaked in another pitch so he devised hand signals that would enable him to keep his focus on the pitcher. The signalling proved useful to all players and quickly spread.

Today more than 1,000 silent instructions are given, from catcher to pitcher, coach to batter or fielder, fielder to fielder, and umpire to umpire during a regular nine-inning baseball game.

Today more than 1,000 silent instructions are given, from catcher to pitcher, coach to batter or fielder, fielder to fielder, and umpire to umpire during a regular nine-inning baseball game.

Receive your weekly copy of the Disability Digest.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact