Dear Reader

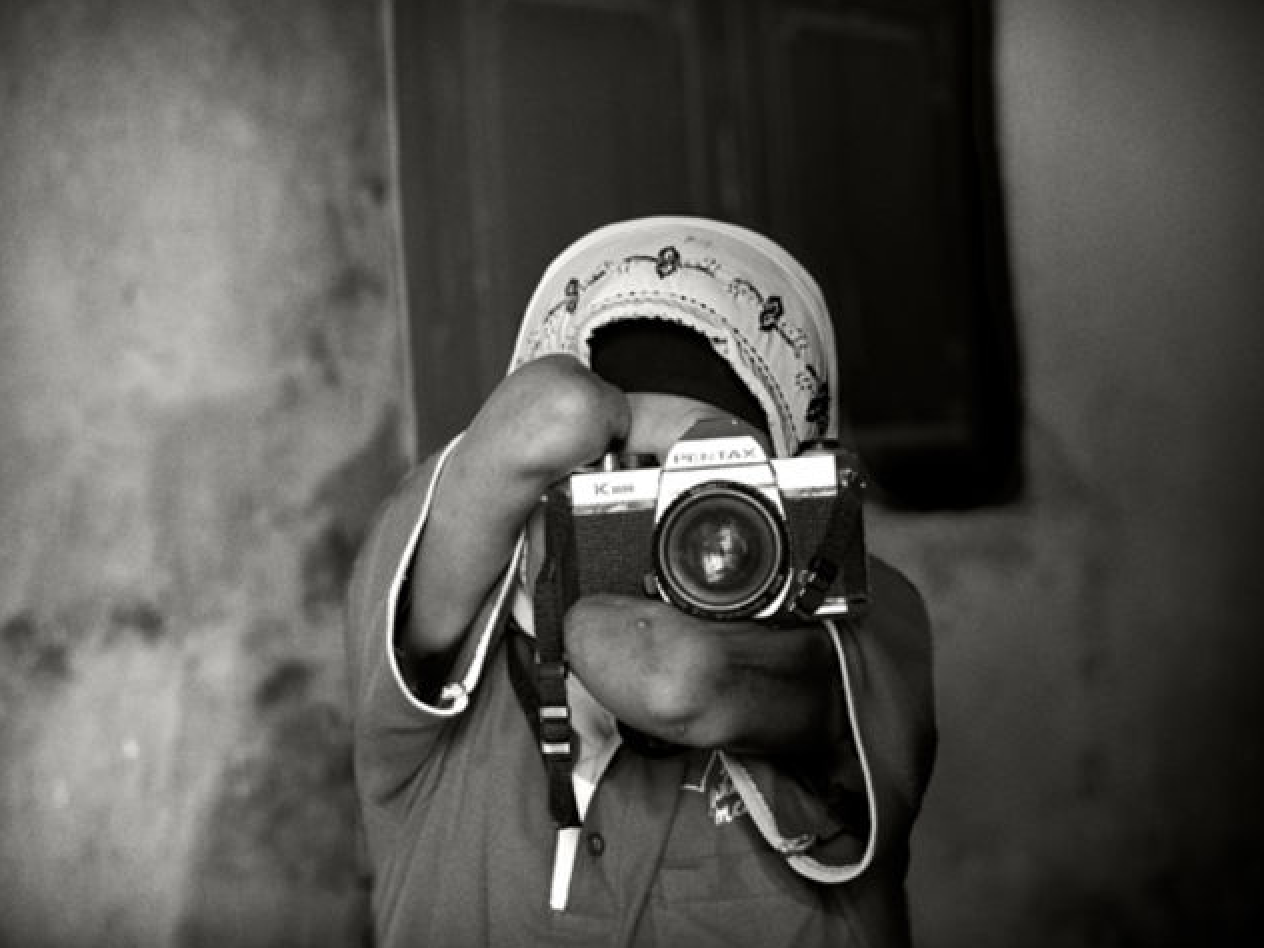

The photograph that graces this issue of the Digest is by Indonesian freelance photographer, Rusidah Badawi. Badawi was born without forearms and works with film, not digital. She uses a modified camera with a screw on the shutter button to make it easier for her to operate.

Also featured are Alexander Pope one of the most quoted writers in the English language, poet Jane Kenyon author of the famous poem Having it out with Melancholy and the “tricycle suffragette,” May Billinghurst.

The biases of storytellers and historians influence who and what we value in the present day. Unless we correct what history has overlooked these biases will continue into the future.

Please send your ideas for future issues via this form.

Enjoy– Al

PS: check out my new podcast series The Power of Disability. This week’s guest is Rabia Khedr the activist who “wears many hijabs.” Rabia is co-chair of the “Disability Without Poverty Initiative,” a national movement to ensure that the federal government follows through on its promise to establish a Canada Disability Benefit. “Being blind, I see things differently,” says Rabia.

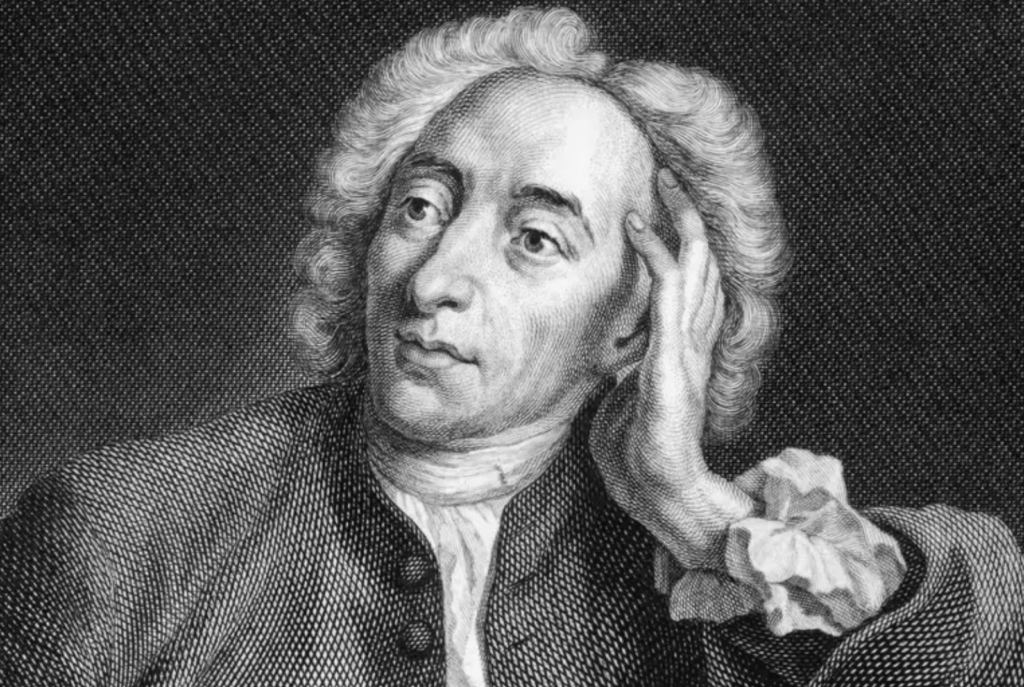

May 21 is the birthday of Alexander Pope the English poet and satirist (1688). He had a quick wit and a gift for memorable phrases. He is the second most quoted writer in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations after Shakespeare. He was largely self-educated because in those days Catholics were not admitted to universities. He taught himself to read in Latin, Greek, French and Italian and began churning out verse before he became a teenager.

Pope wasn’t afraid to express his opinions in public particularly about the wealthy. “We may see the small value God has for riches, by the people he gives them to,” he said. In return, the recipients of his satire described him as “the most notorious hunchback of the 18th century”. Pope seldom referred to his disability in his writing. One rare example is, “I cough like Horace, and tho lean, am short.” He was four feet six inches tall (1.4 metres.) Nowadays people speculate that he contracted spinal tuberculosis which limited his growth and caused his spine to curve.

His Essay on Criticism gave us many well-known proverbs: “To err is human; to forgive, divine,” “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread,” and “A little learning is a dangerous thing. Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring.” In Greek mythology, the Pierian Spring was the fountain of knowledge.

Pope died on May 30, 1744. He is considered one of the greatest English poets of all time. I can’t resist another quote: “Teach me to feel another’s woe, to hide the fault I see, that mercy I to others show, that mercy show to me.”

May 23 is the birthday of New Hampshire’s poet laureate, Jane Kenyon (1947). Kenyon’s poetry books sold well. She appealed to a devoted readership because of her confident, plain language writing style. She seldom used metaphors and focused on everyday life and the natural world around her. “For me, poetry comes out of silence,” she said.

Kenyon wrote regularly about her lifelong struggle with depression. Her most famous poem in that regard is “Having it out with Melancholy” which appeared in her last collection of poetry, Constance.

The poem opens with a quote from Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard: “If many remedies are prescribed for an illness, you may be certain that the illness has no cure.”

Kenyon begins by describing depression’s constant presence in her life:

When I was born, you waited

behind a pile of linen in the nursery,

and when we were alone, you lay down on top of me, pressing

the bile of desolation into every pore.

And from that day on

everything under the sun and moon

made me sad — even the yellow

wooden beads that slid and spun

along a spindle on my crib.

She refers to her depression as a “mutilator of souls,” “an unholy ghost,” and a “crow who smells hot blood.”

Day and night

I feel as if I had drunk six cups

of coffee, but the pain stops

abruptly. With the wonder

and bitterness of someone pardoned

for a crime she did not commit

I come back to marriage and friends,

to pink fringed hollyhocks; come back

to my desk, books, and chair.

The poem ends with a description of her “ordinary contentment”:

What hurt me so terribly

all my life until this moment?

How I love the small, swiftly

beating heart of the bird

singing in the great maples;

its bright, unequivocal eye.

Kenyon died of cancer at the age of 47 in 1995. “Tell the whole truth. Don’t be lazy, don’t be afraid, “ she advised writers. “Close the critic out when you are drafting something new. Take chances in the interest of clarity of emotion.”

Click here for Amanda Palmer’s beautiful reading of Having it Out With Melancholia.

May 31 is the birthday of English suffragette and women’s rights advocate Rosa May Billinghurst (1875). She survived polio as a child and got around by wearing leg irons, using crutches and pedalling a modified tricycle by hand. As a young woman, she and her sister began supporting poor children who lived in the slums, and women who lived in what were called workhouses because they could not support themselves. Exposure to those injustices led her to join the suffrage movement which was picking up steam in the early 1900s. “I thought surely if women were consulted in the management of the state, happier and better conditions must exist for hard-working sweated lives such as these… It was gradually unfolded to me that the unequal laws which made women appear inferior to men were the main cause of these evils,” she said.

Billinghurst became known as the “cripple suffragette,” or the “tricycle suffragette,” by the press and her peers. She didn’t hesitate to ram into police officers with her tricycle. Billlinghurst went to jail several times. “This is a women’s war,” she told the jurors at one of her trials, “in which we hold human life dear and property cheap, and if one has to be sacrificed for the other, then we say let property be destroyed and human life be preserved.”

On another occasion, she, and other imprisoned suffragettes, went on a hunger strike. Authorities tried to force feed them through the nose. Billinghurst became so ill she was released after two weeks. “The government may further maim my crippled body by the torture of forcible feeding, as they are torturing weak women in prison today,” she stated at a subsequent trial. “They may even kill me in the process, for I am not strong, but they cannot take away my freedom of spirit or my determination to fight this good fight to the end.”

The first stage of the good fight ended in 1918, when property-owning women age 30 and older were given the right to vote in England. Ten years later, women 21 and older were given the same voting rights as men. Little is known of Billinghurst’s life after these achievements. She died on July 29, 1953, at the age of 78. “We are not hooligans seeking to destroy but we mean to wake the public mind from its apathy,” she said.

Did you know?

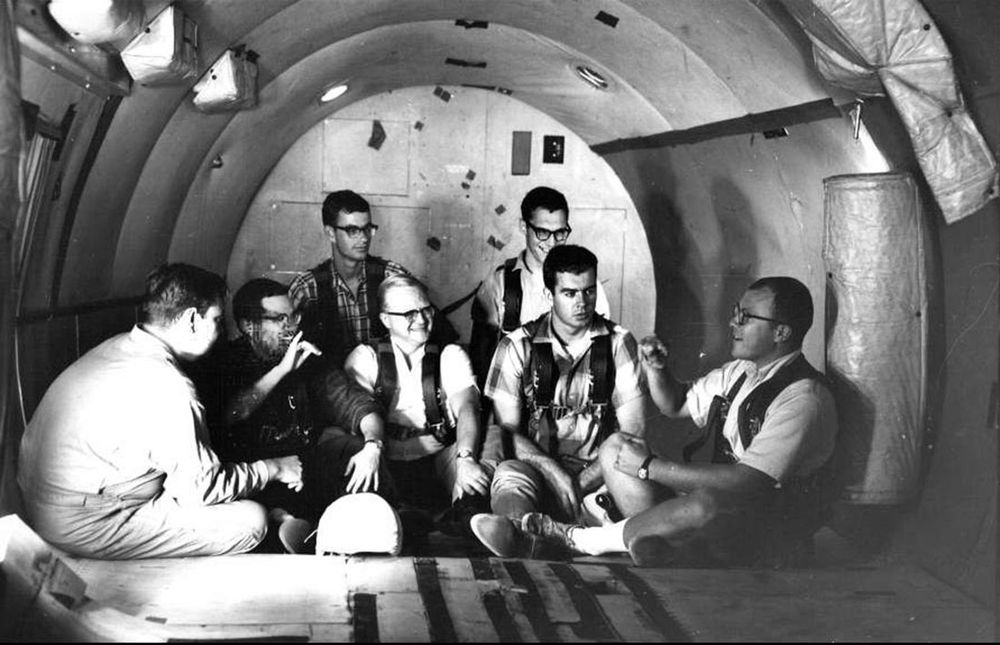

NASA has relied on the insights of people with disabilities since the origins of the space program. In the late 1950s, they recruited eleven men from Gallaudet College (now Gallaudet University), a school for d/Deaf students to test how the body might react to the stomach-churning rigours of spaceflight. NASA needed people who were immune to motion sickness and the Gallaudet Eleven fit the bill because spinal meningitis had damaged their inner ear. Some of these space pioneers are pictured about in a zero-gravity aircraft.

“We were different in a way they needed,” said Harry Larson one of the Gallaudet Eleven. Even the famous John Glenn one of America’s first astronauts was envious of their ability to not get sick during the punishing tests they were all subjected to.

Receive your weekly copy of the Disability Digest.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact