Dear Reader

Disability is written out of history either by ignoring the contributions of persons with disability or by separating their disability from their contributions. This issue of the Disability Digest is still in beta mode as we strive for improvements. Please send your comments and suggestions via this form. And if you like what you’re reading do spread the word.

Thanks – Al

This week in history ...

On January 30 1882, future US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) was born. At the age of 39 while vacationing in New Brunswick he fell ill and was diagnosed with polio. When he returned to politics few understood he was paralyzed below the waist and could not walk on his own. They thought he had recovered. That’s because Roosevelt stage managed his appearances for fear the designation “cripple”would end his political career. On his inauguration day he rolled to the stage in his wheelchair hidden by a barrier. He walked the last few steps supported by his aides. He had hand controls in his cars so he could be seen driving. And he banned anyone from taking pictures of him with his braces, wheelchair or canes. (The picture above is one of the few ever taken of him sitting in a wheelchair.)

On January 30 1882, future US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) was born. At the age of 39 while vacationing in New Brunswick he fell ill and was diagnosed with polio. When he returned to politics few understood he was paralyzed below the waist and could not walk on his own. They thought he had recovered. That’s because Roosevelt stage managed his appearances for fear the designation “cripple”would end his political career. On his inauguration day he rolled to the stage in his wheelchair hidden by a barrier. He walked the last few steps supported by his aides. He had hand controls in his cars so he could be seen driving. And he banned anyone from taking pictures of him with his braces, wheelchair or canes. (The picture above is one of the few ever taken of him sitting in a wheelchair.)

Those who knew FDR believed his disability prepared him to lead the American people through the depression, World War 2 and the implementation of the New Deal. His Secretary of State Francis Perkins said FDR emerged from rehabilitation, “completely warm-hearted, with a new humility of spirit.” Roosevelt was much blunter. “Once you’ve spent two years trying to wiggle one toe, everything is in proportion,” he said.

Illustrating the the power of vulnerability Roosevelt observed, “Human kindness has never weakened the stamina or softened the fibre of a free people. A nation does not have to be cruel to be tough.”

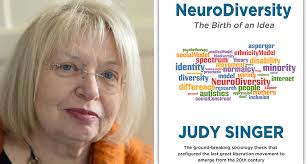

On February 1st 1998 Australian author and sociologist Judy Singer introduced the term neurodiversity to the world. In her chapter, Why Can’t you be Normal for Once in Your Life? she wrote: “The neurologically different represent a new addition to the familiar political categories of class/gender/race and will augment the insights of the social model of disability. The rise of neurodiversity takes postmodern fragmentation one step further… even our most taken-for granted assumptions: that we all more or less see, feel, touch, hear, smell, and sort information, in more or less the same way, (unless visibly disabled) – are being dissolved.”

Journalist Steve Silberman described “Neurodiversity” as the rallying cry of the first new civil rights movement to take off in the 21st century.”

On February 2nd 2005 Jordan River Anderson died. Jordan was from Norway House, Cree Nation in the province of Manitoba. He was born with multiple disabilities and spent all five years of his short life in hospital instead of in a loving home because the Canadian and Manitoba governments couldn’t agree on who should pay for his support. In his memory the Canadian House of Commons passed Jordan’s Principle, a legal obligation to provide First Nations children with the support they need as soon as they need them. Jordan’s Principle requires that the government department of first contact pay for the services without delay or disruption. The paying government can then refer to an intergovernmental process to pursue repayment.

On February 2nd 2005 Jordan River Anderson died. Jordan was from Norway House, Cree Nation in the province of Manitoba. He was born with multiple disabilities and spent all five years of his short life in hospital instead of in a loving home because the Canadian and Manitoba governments couldn’t agree on who should pay for his support. In his memory the Canadian House of Commons passed Jordan’s Principle, a legal obligation to provide First Nations children with the support they need as soon as they need them. Jordan’s Principle requires that the government department of first contact pay for the services without delay or disruption. The paying government can then refer to an intergovernmental process to pursue repayment.

The First Nation’s Child and Family Caring Society led the campaign to honour Jordan’s memory. It’s Executive Director Cindy Blackstock said: “Jordan could not talk, yet people around the world heard his message. Jordan could not breathe on his own and yet he has given the breath of life to other children. Jordan could not walk but he has taken steps that governments are just now learning to follow.”

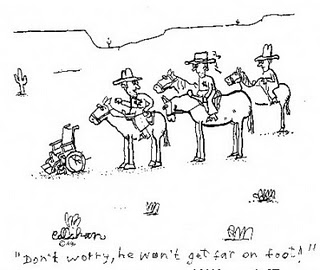

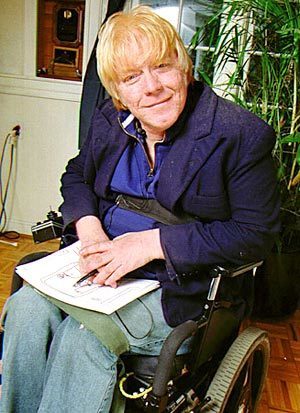

On February 5th 1951 the cartoonist John Callahan was born. At the peak of his popularity his cartoons appeared in more than two hundred newspapers. Callahan became a quadriplegic at the age of 21 when both he and the driver were on a drinking spree and crashed into a telephone pole. He credits his dark humour for bringing him out of his depression after the accident. His cartooning style was described as politically incorrect. His cartoons occasionally led to boycotts and protests. The cartoons targeting people with disabilities were among his most controversial although not to those with disabilities. ”My only compass for whether I’ve gone too far is the reaction I get from people in wheelchairs, or with hooks for hands,” said Callahan. “Like me, they are fed up with people who presume to speak for the disabled. All the pity and patronizing. That’s what is truly detestable.”

On February 5th 1951 the cartoonist John Callahan was born. At the peak of his popularity his cartoons appeared in more than two hundred newspapers. Callahan became a quadriplegic at the age of 21 when both he and the driver were on a drinking spree and crashed into a telephone pole. He credits his dark humour for bringing him out of his depression after the accident. His cartooning style was described as politically incorrect. His cartoons occasionally led to boycotts and protests. The cartoons targeting people with disabilities were among his most controversial although not to those with disabilities. ”My only compass for whether I’ve gone too far is the reaction I get from people in wheelchairs, or with hooks for hands,” said Callahan. “Like me, they are fed up with people who presume to speak for the disabled. All the pity and patronizing. That’s what is truly detestable.”

Callahan may have enjoyed pushing buttons but he was deeply religious. He described what he did as survivor humour. “All these things that happened to me in my life, they have deepened life for me,” he told a reporter. “I draw things that are real to me. That includes death, poverty and sickness, as well as love, profit and religion.” Callahan died on July 24, 2010.

Callahan’s memoir Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot was made into a movie of the same name starring Joaquin Phoenix.

Did you know?

Enlightenment reformers in the late 1700s embraced difference caused by disability and recognized its ability to create a richer, deeper and fuller world. They believed, for example, that blindness was a social asset and that people who were blind had unique and important talents. Jean-Jacques Rousseau thought that the ability to navigate without eyesight should be an important part of everyone’s education because it would heighten the other senses.